From the Winter 2025 edition of Gurls to the Front! A Q&A with Rebecca Campbell

Every story in this collection begins with Story Notes that sort of explain the premise of each story or your aim in writing the story. What made you decide to include those rather than just throwing the reader into each story’s world?

Selena at Stelliform suggested the notes and the introductory essay as a way to clarify how the stories are connected to one another. I probably wouldn’t have done it without her suggestions, so there’s a reminder of how much writing is a collaboration (if you’re lucky with your editor). The paratext also ended up clarifying my goals and preoccupations as a writer, too, which I hadn’t expected. I realized how often I am drawn to certain images: rainforests, saltwater, ghosts. And I enjoy meditations on stories, like the brief essay introducing “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” in Ursula le Guin’s The Wind’s Twelve Quarters.

In the story notes for the final story in this collection, you say that it “defines [your] goals for the collection: it is a story about possibility and transformation, even in pain.” Can you elaborate a bit on what your goals were for the collection as you were writing it or maybe as you were deciding on which of your stories to include in this book?

These stories were written over more than a decade, through grad school, the birth of my son, and a pandemic. Often, they’re about the distance I felt from my home. The distance was painful, but also powerful—maybe because memory simplifies things? Or because we only remember what’s important when we’re far from home? I’m not quite sure, actually. That sense of connection and separation from place ended up being a throughline for the collection. I'm also preoccupied with transformation, whether it was biological, political, or emotional. I ended up ordering the stories chronologically, from the recent past to the near future, and found they also followed a life, from childhood through adolescence, adulthood, and into old age. The stories that begin and end the collection seemed like bookends, to me, taking a much wider view, but still exploring the ways we can change.

Can you tell me a bit about your research process? Many, if not all, of these stories seem to involve a lot of thorough research—“Wider Than the Sky, Deeper Than the Sea,” which involves humans being fitted with technology to sense the way various animals do, comes to mind—and I wonder how much time you spend on the research, do you have a clear idea of what the story will be when you embark on research or does the story come out of what you find during your research process, etc.?

I cannot overstate how much I love research. Like, I love research. I’m constantly browsing around books and journals for fascinating bits and pieces—history, ecology, neuroscience, archaeology, folklore, critical theory. I love to play with the implications of some new information. And, maybe even more than that, research gives me a little insight into other ways of being, whether that’s an animal umwelt or another human experience. That also makes me feel a little less limited to my own body, mind, or place in the world. It’s the same reason I read fiction, I guess: to learn something new from a perspective that isn’t my own. My writing is constantly changed by what I learn, and stories are often redirected as I research some corner of the world and learn something that makes my initial idea impossible or just more complicated than I had originally thought. It’s a wonderful kind of collaboration—not with another writer or an editor, but with reality as it is slowly revealed.

Many of these stories explore an unsettling future—“Such Thoughts are Unproductive” deals with AI and its potential overreach in particular. I wonder if you could share some of your thoughts on our future with AI, the future of writers and the paid work they’ll be able to do, for instance, and in general, the future of creativity and of our (or maybe future generations who are now using ChatGPT to come up with ideas for them) ability to produce creative thought. I’ve spoken with some writers who feel very positive about our future with AI and many others (myself among them) who are quite afraid.

This is such a weird moment to be a writer, as our work gets chomped up by LLMs (large language models) that are obscenely expensive, and generate a bunch of words without value to anyone. However, my worries about AI writing are less about the material generated than they are about the loss of process. In university composition classrooms, I tried to teach writing as a process—that we write, we read, we re-write, discover, re-discover, uncover, and transform. The point of the text isn’t the final arrangement of words, but the process by which we got there. I don’t understand the point of writing if you skip that process. Maybe I’m feeling anticipatory grief for everyone who won’t get a chance to do that because a money-crazed corporation has decided writing is just a bunch of marks on a page.

Finally, these stories I think are all set on Vancouver Island, or are deeply rooted in the West coast atmosphere and ecology. I think you grew up here, but just recently moved back from being in Ontario. Can you talk a bit about what the West coast environment means to you, how it felt to be away, and how it felt to return? Do you think this environment will inspire what you write next?

I’ve only been back for a few months, but I already feel it changing the way I write. I keep having these strange moments of almost uncanny familiarity— a scent, an angle of light, a texture in the air— that make me feel like I never left. Mount Baker remains on the horizon exactly where I left it, and the sea lions are still arfing away in Saanich inlet.

Sometimes I think I’m neurotically obsessed with place. I used to feel painfully homesick when I smelled grand fir. I have recurring dreams about the length of road between the house I grew up in and my grandparents’ house. I watched wildfire reports with dread from the other side of the country. A lot of my stories explore what it means to belong to a place, particularly as a settler. Back when I wrote academically, I worked on memory and landscape—dream topographies and lieux de mémoire and commemoration. Now, though, I explore space and memory through stories rather than analysis. I think it’s the same impulse, though.

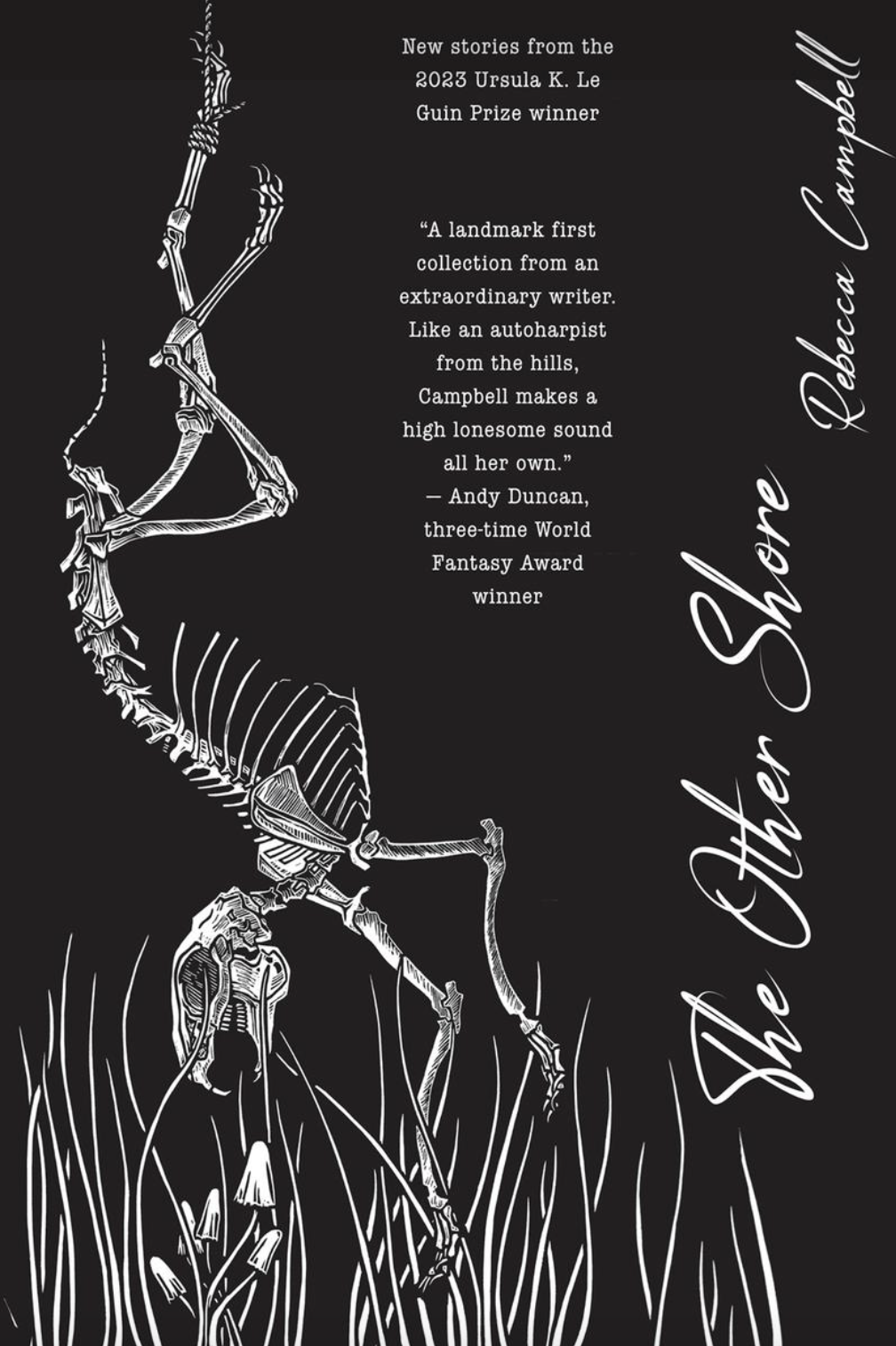

Rebecca Campbell is a Canadian writer of weird fiction. Her work has appeared in The Year’s Best Science Fiction, The Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy, The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, and The Best Science Fiction of the Year, Volumes 5 & 6, in addition to many contemporary magazines, including The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Clarkesworld, and Interzone. She won the Sunburst award for short fiction in 2020 for “The Fourth Trimester is the Strangest" and the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award in 2021 for “An Important Failure.” In 2023, her novella, Arboreality, won the Ursula le Guin Prize. The Other Shore from Stelliform Press is her first collection of short stories.